Spectrum (homotopy theory)

In algebraic topology, a branch of mathematics, a spectrum is an object representing a generalized cohomology theory. There are several different constructions of categories of spectra, any of which gives a context for the same stable homotopy theory.

Contents |

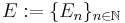

The definition of a spectrum

There are many variations of the definition: the treatment here is close to that in Adams (1974). A spectrum is a sequence  of CW-complexes together with inclusions

of CW-complexes together with inclusions  of the suspension

of the suspension  as a subcomplex of

as a subcomplex of  .

.

Functions, maps, and homotopies of spectra

There are three natural categories whose objects are spectra, whose morphisms are the functions, or maps, or homotopy classes defined below.

A function between two spectra E and F is a sequence of maps from En to Fn that commute with the maps ΣEn→En+1 and ΣFn→Fn+1.

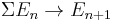

Given a spectrum  , a subspectrum

, a subspectrum  is a sequence of subcomplexes that is also a spectrum. As each i-cell in

is a sequence of subcomplexes that is also a spectrum. As each i-cell in  suspends to an (i+1)-cell in

suspends to an (i+1)-cell in  , a cofinal subspectrum is a subspectrum for which each cell of the parent spectrum is eventually contained in the subspectrum after a finite number of suspensions. Spectra can then be turned into a category by defining a map of spectra

, a cofinal subspectrum is a subspectrum for which each cell of the parent spectrum is eventually contained in the subspectrum after a finite number of suspensions. Spectra can then be turned into a category by defining a map of spectra  to be a function from a cofinal subspectrum

to be a function from a cofinal subspectrum  of

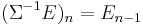

of  to F, where two such functions represent the same map if they coincide on some cofinal subspectrum. Intuitively such a map of spectra does not need to be everywhere defined, just eventually become defined, and two maps that coincide on a cofinal subspectrum are said to be equivalent. This gives the category of spectra (and maps), which is a major tool. There is a natural embedding of the category of pointed CW complexes into this category: it takes

to F, where two such functions represent the same map if they coincide on some cofinal subspectrum. Intuitively such a map of spectra does not need to be everywhere defined, just eventually become defined, and two maps that coincide on a cofinal subspectrum are said to be equivalent. This gives the category of spectra (and maps), which is a major tool. There is a natural embedding of the category of pointed CW complexes into this category: it takes  to the suspension spectrum in which the nth complex is

to the suspension spectrum in which the nth complex is  .

.

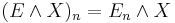

The smash product of a spectrum  and a pointed complex

and a pointed complex  is a spectrum given by

is a spectrum given by  (associativity of the smash product yields immediately that this is indeed a spectrum). A homotopy of maps between spectra corresponds to a map

(associativity of the smash product yields immediately that this is indeed a spectrum). A homotopy of maps between spectra corresponds to a map  , where

, where  is the disjoint union

is the disjoint union ![[0, 1] \sqcup \{*\}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f183deee3a61432ce2f60bc327aa6b40.png) with * taken to be the basepoint.

with * taken to be the basepoint.

The stable homotopy category, or homotopy category of (CW) spectra is defined to be the category whose objects are spectra and whose morphisms are homotopy classes of maps between spectra. Many other definitions of spectrum, some appearing very different, lead to equivalent stable homotopy categories.

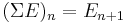

Finally, we can define the suspension of a spectrum by  . This translation suspension is invertible, as we can desuspend too, by setting

. This translation suspension is invertible, as we can desuspend too, by setting  .

.

The triangulated homotopy category of spectra

The stable homotopy category is additive: maps can be added by using a variant of the track addition used to define homotopy groups. Thus homotopy classes from one spectrum to another form an abelian group. Furthermore the stable homotopy category is triangulated (Vogt (1970)), the shift being given by suspension and the distinguished triangles by the mapping cone sequences of spectra

.

.

Smash products of spectra

The smash product of spectra extends the smash product of CW complexes. It is somewhat cumbersome to define. It makes the stable homotopy category into a monoidal category; in other words it behaves like the tensor product of abelian groups. A major problem with the smash product is that obvious ways of defining it make it associative and commutative only up to homotopy. Some more recent definitions of spectra eliminate this problem, and give a symmetric monoidal structure at the level of maps, before passing to homotopy classes.

The smash product is compatible with the triangulated category structure. In particular the smash product of a distinguished triangle with a spectrum is a distinguished triangle.

Generalized homology and cohomology of spectra

We can define the (stable) homotopy groups of a spectrum to be those given by

![\displaystyle \pi_n E = [\Sigma^n S, E]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/acea5ac89c004fa74207710217a2ab10.png) ,

,

where  is the spectrum of spheres and

is the spectrum of spheres and ![[X, Y]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ab4fc7097880a47a3c8db15b20f8ff3d.png) is the set of homotopy classes of maps from

is the set of homotopy classes of maps from  to

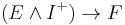

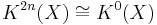

to  . We define the generalized homology theory of a spectrum E by

. We define the generalized homology theory of a spectrum E by

and define its generalized cohomology theory by

![\displaystyle E^n X = [\Sigma^{-n} X, E]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e808e3058d6fc5d26d196495a2371d6d.png) .

.

Here  can be a spectrum or a (by using its suspension spectrum) a space.

can be a spectrum or a (by using its suspension spectrum) a space.

Examples

Consider singular cohomology  with coefficients in an abelian group A. By Brown representability

with coefficients in an abelian group A. By Brown representability  is the set of homotopy classes of maps from X to K(A,n), the Eilenberg-MacLane space with homotopy concentrated in degree n. Then the corresponding spectrum HA has n'th space K(A,n); it is called the Eilenberg-MacLane spectrum.

is the set of homotopy classes of maps from X to K(A,n), the Eilenberg-MacLane space with homotopy concentrated in degree n. Then the corresponding spectrum HA has n'th space K(A,n); it is called the Eilenberg-MacLane spectrum.

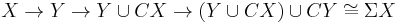

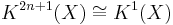

As a second important example, consider topological K-theory. At least for X compact,  is defined to be the Grothendieck group of the monoid of complex vector bundles on X. Also,

is defined to be the Grothendieck group of the monoid of complex vector bundles on X. Also,  is the group corresponding to vector bundles on the suspension of X. Topological K-theory is a generalized cohomology theory, so it gives a spectrum. The zero'th space is

is the group corresponding to vector bundles on the suspension of X. Topological K-theory is a generalized cohomology theory, so it gives a spectrum. The zero'th space is  while the first space is

while the first space is  . Here

. Here  is the infinite unitary group and

is the infinite unitary group and  is its classifying space. By Bott periodicity we get

is its classifying space. By Bott periodicity we get  and

and  for all n, so all the spaces in the topological K-theory spectrum are given by either

for all n, so all the spaces in the topological K-theory spectrum are given by either  or

or  . There is a corresponding construction using real vector bundles instead of complex vector bundles, which gives an 8-periodic spectrum.

. There is a corresponding construction using real vector bundles instead of complex vector bundles, which gives an 8-periodic spectrum.

For many more examples, see the list of cohomology theories.

History

A version of the concept of a spectrum was introduced in the 1958 doctoral dissertation of Elon Lages Lima. His advisor Edwin Spanier wrote further on the subject in 1959. Spectra were adopted by Michael Atiyah and George W. Whitehead in their work on generalized homology theories in the early 1960s. The 1964 doctoral thesis of J. Michael Boardman gave a workable definition of a category of spectra and of maps (not just homotopy classes) between them, as useful in stable homotopy theory as the category of CW complexes is in the unstable case. (This is essentially the category described above, and it is still used for many purposes: for other accounts, see Adams (1974) or Vogt (1970).) Important further theoretical advances have however been made since 1990, improving vastly the formal properties of spectra. Consequently, much recent literature uses modified definitions of spectrum: see Mandell et al. (2001) for a unified treatment of these new approaches.

References

- Adams, J. F.(1974), "Stable homotopy and generalised homology". University of Chicago Press

- Atiyah, M. F.(1961), "Bordism and cobordism", Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 57: 200-208

- Elmendorf, A. D.; Kříž; Mandell, M. A.; May, J. Peter (1995), "Modern foundations for stable homotopy theory", in James., I. M., Handbook of algebraic topology, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 213–253, doi:10.1016/B978-044481779-2/50007-9, ISBN 978-0-444-81779-2, MR1361891, http://www.math.uchicago.edu/~may/PAPERS/Newfirst.pdf

- Lima, Elon L. (1959), "The Spanier-Whitehead duality in new homotopy categories", Summa Brasil. Math. 4: 91–148, MR0116332

- Lages Lima, Elon (1960), "Stable Postnikov invariants and their duals", Summa Brasil. Math. 4: 193–251

- Mandell, M. A.; May, J. P.; Schwede, S.; Shipley, B. (2001), "Model categories of diagram spectra", Proc. London Math. Soc. (3) 82 (2): 441–512, doi:10.1112/S0024611501012692

- Vogt, Rainer (1970), Boardman's stable homotopy category, Lecture Notes Series, No. 21, Matematisk Institut, Aarhus Universitet, Aarhus, MR0275431, http://books.google.com/books?id=xlvvAAAAMAAJ

- Whitehead, George W. (1962), "Generalized homology theories", Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 102 (2): 227–283, doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-1962-0137117-6

![E_n X = \pi_n (E \wedge X) = [\Sigma^n S, E \wedge X]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ce4d6c02a7c922eed93a06526b70bc4a.png)